Finnish Mosin-Nagant m91

|

||||||||||||||||||||

| Mosin-Nagant 91 (Finnish) | |

| Type: | Bolt Action Rifle |

| Caliber: | 7.62 x 54R |

| Capacity: | 5 |

| Barrel Length: | 31 1/2 in. |

| Overall Length: | 51 3/8 in. |

| Weight: | apx 9.5 lbs. |

| Sights: | Tangent Rear, Blade Front |

| Finish: | Blue |

| Market Price: | $150-$250 |

What caught my eye on this rifle was not the fact that it was a Mosin-Nagant. Generally, speaking, they're a dime a dozen. What drew me to this one was the fact that it appeared to have some characteristics that were somewhat rarer than normal. First, as already noted, it was a 91 with Tzarist markings. Second, it appeared at first glance to be in original condition and had matching serial numbers. (But something didn't quite add up. More on that later.) Third, the stock contained a cutout for a regimental badge. Add all that up, and this rifle has a significant amount of history associated with it.

Well, having less than $100 in my wallet with some of that allocated already, I could not buy this then and there but fortunately, the fellow who was selling it was a local and fully prepared for this eventuality. He had no issue meeting up with me the following weekend for the requisite exchange of currency, even declining my offer to provide him with a small holding fee from what cash I did have on hand. It's nice to know that there are still honest gentlemen in this world willing to do business on nothing more than a handshake. The following Saturday, the rifle was mine.

A Brief History

So whats the deal with Finnish Mosin-Nagant rifles? Well, in the early 19th century, after Sweden declined as a regional power, it and Finland were conquered by Russia, recalling that at that point, Finland was not yet an independant state and merely a collection Swedish provinces. It was after Russia invaded that it became an autonomous region and a Grand Duchy of Russia. The people of this region were actually given a fair degree of autonomy, retaining their language (which was actually Swedish at that time), religion, and cultural identity.

Over the course of years, there was an awakening of self and a national movement arose. In 1863, the administrative language was officially changed to Finnish by Alexander II. Over the next roughly fifty years, the every day language slowly changed to Finnish as well. In 1878, through the Conscription Act, Finland established its own army. Being a Grand Duchy of Russia, it should surprise no one that this army was equipped with Russian rifles. But with that act, it was also just a matter of time before something boiled over.

The autonomy of the Finnish state (independant currency, legislature, even an official boundry seperating it from the Russian empire) had been a sore point with Russia for a while. While Alexander III sat on the Russian throne, he set about to do something about it. Tzar Nicholas II continued these policies when he ascended in 1894. Russification was now the order of the day.

But Russia had had its own problems slowly rumbling beneath the surface of society. For generations, the peasant class in Russia had suffered greatly while the nobility lived lavishly. Such things are common in kingdoms but even in the best of times, life could be hard on the Russian steppes. To have that hard life made almost unbearable by the demands of the crown, the peasants even being looked on as mere animals by some members of the nobility (remember Ivan?), resulted in mounting frustration. In 1905, after the embarrassment of the Russo-Japanse war, these frustrations boiled over, temporarily taking the pressure off of Finland. Recall that Russia had to deal with problems in other provinces as well. Shortly thereafter, the world found itself in the grips of WWI and most other European issues took a back seat. Russia, thus distracted and burdened by the demands of this new type of war, further declined culminating in the Bolshevik revolution in October 1917. Finland, at the end of that year, ultimately declared indepenance from Russia. (Obviously, that wasn't going to go over well but Russia did not have the ability to respond to the declaration at that time.)

Immediately after this declaration, the rift between leftists and conservatives became a gulf. Just over a month after declaring of independance, at the end of January, 1918, Finnish Bolsheviks staged a coup and forced the government to flee Helsinki. For the next four months, civil war raged between communist and anti-communist forces, but at the end of May, government troops were able to declare victory and establish themselves as a republic in 1919 and, for a time, things were relatively peaceful. Finland and Russia even signed a non-aggression pact in 1932, guarenteeing a measure of stability for the fledgeling republic. During this period, Finland acquired additional M1891s from countries such as Hungary, Czecheslovakia, and Poland.

During the 1930s, however, Hitler was firmly in power and Nazi Germany was on the rise. In 1938, with German anexation of Austria and the polices of appeasement in full force, it became clear that another major war was inevitable. In August, 1939, Germany and Russia signed a non-aggression of their own which also contained a secret clause declaring Finland to be within the sphere of Soviet influence. When the Soviet Union wanted to establish military bases on Finnish soil, the Finns flatly refused. The result was Russia's withdrawl from the non-aggression pact and invasion at the end of November, 1939. During this year, another larger batch of rifles was purchased from Yugoslavia, refurbishing these new acquisitions as necessary which in many instances required fabrication of new barrels or relining of existing barrels and production of new stocks.

Hostilities in what became known as "The Winter War" ended in March with the Soviets acquiring Southeastern Finland. In this conflict, the Finnish military captured what is estimated at a bit shy of 30,000 M1891 rifles from the Soviets, not counting those picked up on the battlefield. Despite surprisingly effective resistance and inflicting heavy casualties on the Russian military, the outcome was innevitable since, with Germany on the move and the spectre of Japan still looming in the far east, the other nations of the world, whose militaries either as yet were unprepared for the new conflict or already stretched to the limit, sent only sympathy to Finland and left them to fight on their own.

Throughought the 1920s and 1930s, the Finnish continued to experiment with improvements to the Russian rifles. Sometimes these were little more than replacing certain parts, others were a near complete rebuild. Like the Russians, the Finnish saw a need for sniper rifles and designs for these too were part of the experimentation. Some captured or purchased rifles were used as a base for these experiments while others were used as spare parts for repairs and other projects.

When Germany invaded Russia in the summer of 1941, Finland saw an opportunity to regain their lost lands and fought the Soviet Union as a co-belligerant with Germany in what is known as "The Continuation War." The effort, unfortunately, proved futile and in 1944, when the armistice was signed, Finland was forced to cede yet more territory to Russia. These terms were affirmed in the Paris peace treaty of 1947. From this conflict, an estimated 360,000 rifles were captured, again, serving as spare parts and platforms for experimentation and improvement. It must be remembered, that in all the battles fought that the capture of hardware went both ways with the Russians obtaining a fair number of Finnish rifles through the same means.

Despite this loss of territory, the end result was stability. In the years following WWII, Finland has taken its rightful place as a member of the United Nations and the European Union, and has become a thriving society. It should be remembered by all though that the prosperity now enjoyed was earned through struggles and strife and paid for with blood.

Evaluating My Purchase

My first task with any such procurement is a detail strip and cleaning and subsequent inspection, looking for damaged parts and any markings I can find to help authenticate the various pieces and confirm that they are appropriate to the vintage of the rifle. One of the first things I spotted was the importer's mark, which I had not noticed before. (It's very subdued.) This was somewhat disappointing as I had hoped that this rifle had made it to this country through other means at an earlier date but it was immediately obvious that these marks were placed on the rifle under a different set of laws. There was only one "new" serial number and that was on the butt plate. The importer's stamp was on the right side of the barrel, just behind the front sight. So while finding that was not exactly what I had hoped for, the fact that they are minimal makes me very happy.

Tear down of this rifle was job in and of itself. It was a real challenge to remove a couple of the screws without (further) damaging them. Judging on how difficult it was to separate certain parts and from the volume of crud found, I do not believe that it had ever been cleaned since it was brought into this country. It was stated to me that the entire time the seller owned this rifle (at least 25 years), it had not once been fired but had merely been stored or displayed.

A proper, careful cleaning of any historic arm is very necessary to the preservation of the arm, as is periodic repetition and inspection. Case in point, the screw on the back of the receiver was litterally rusted in place. (There's a good reason rifles are covered in cosmoline during long term storage.) Now that I have freed it, I have the opportunity to clean that rust off and halt further oxidation by properly treating the affected parts and storing them in a low humidity environment. You will likely not be able to remove all the rust and still preserve the integrity of any weapon as a collectible. Doing so can also damage the finish. Remember, blueing is a form of rust. Rust removers and wire brushes will take the blueing off too and you'll be worse off than before. What you're interested in is only preventing further deterioration. This is preservation, not restoration or refurbishing.

A good three or four hours later, it was clear to me that the rifle was not all original parts as originaly thought although the parts themselves are in reasonably good condition, except for missing the hand guard. My rifle, as noted, has a 1914 barrel from the Tula arsenal. The receiver, barrel, and bolt all bear a 317 serial number. During earlier production, the Russians would reset serial number sequences at the start of each year. That means that the serial number itself cannot be used to date the earlier rifles. However, in this case, the fact that they all match and that there is no evidence of overstriking of any mark on any of these three parts as was common during arsenal refurbishing would suggest that they were original to the rifle but even this must be taken with a grain of salt. You see, while they match, careful attention to detail shows that the numbers on the three pieces use different fonts. This could be completely innocuous since the numbers give some appearance of having been struck by hand and, not knowing the operation of the assembly plant, it is entirely possible they were struck at different points during assembly. This, though, is unlikely in at least one instance as indicated below.

Markings found vary and reflect parts from several sources. The sight leaf, sight base, nose cap, and forward barrel band bear the Iszhevsk "bow and arrow" stamp. The rear barrel band marking is unclear but could be the Tula hammer except it is not encircled as it should be.

The bolt assembly I found to be a much more amusing story. The bolt itself is from Iszhevsk, the cocking piece is from Tula, and the firing pin is Remington. If the extractor were marked, it wouldn't surprise me to see it too was from somewhere different. The bolt head and firing pin guide bear marks resembling an "E" with the middle line extending left, ending in an arrow point. This is thought to be one of the marks used by Westinghouse during the WWI production contract. So of the five major bolt components, we have four separate sources. This should not occur on a pre-WWI Russian rifle but may be perfectly appropriate on a Finnish rifle. An interesting observation made obvious here is that since design and dimmensions of the bolt did not change, really, parts from one will normally function perfectly in another.

But if you were paying attention you would have noticed a glaring problem for authenticating this rifle. I stated that the barrel bears marks from Tula but the bolt itself, while stamped with the matching serial number, is marked from Izhevsk. "How can this be?" you ask. Well, that's a good question and if you have a plausible answer, I'd love to hear it. Since there is no perceptible evidence of old numbers having been ground off, the best answer I can come up with is that this is a deliberate mating of parts by the Finns. However unlikely this seems, it is entirely possible. The only other reasonable explanation seems to be that the bolt was not marked originally (I have seen this in photos of rifles held by collectors outside the USA) and either marked by the Finns or the importer.

Finnish rifles were a mix of rifles on hand at the time of the Bolshevek revolution, rifles purchased or traded from other nations, captured arms from the Winter War, and rifles refurbished or even produced anew within Finland itself though drawing from certain parts already had in abundance such as receivers. Because of the number of captured weapons going back and forth and with constant refurbishment necessary for such things as damaged sights, broken stocks and hand guards, worn barrels, etc, a rifle "as issued" to a Finnish soldier could well have parts either produced new or borrowed from several different rifles. This history of production and alteration or adaptation of Mosin-Nagant rifles can make classification and identification a bit tricky in some instances. That being the case, it really is not possible to tell when these parts were mixed and matched.

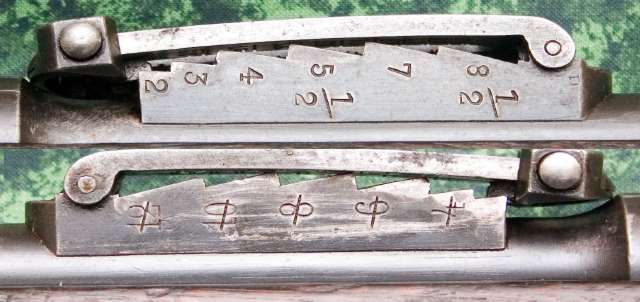

(bottom) Mosin-Nagant rifles were originally sighted in "arshini" which was an imperial unit of measure equal to about 28 inches (0.777 yards.) (top) The Finns changed these marks to approximate meters.

From the date and configuration, this rifle would seem to have originally been a Russian M91 infantry rifle. It is probable that this was obtained either just prior to the Bolshevek revolution or was captured in battle later and reworked by the Finns. That makes this most likely classifiable as a Jalkavaenkivaari m/91. But the fact that it contains the "SA" property stamp which did not come into use until 1942, if it did not simply remain in service for a great many years, it is also possible that this rifle was captured or purchased much later. Note that I am working on the presumption that there were no alterations by the importer other than placing their mark on the rifle. These parts could just as easily have been assembled by them prior to public sale.

The stock has swivel adaptors attached through the Russian sling slots, the Finns prefering swivels over the system used by the Russians. As with all rifles in this category, there is evidence of a screw having been placed in front of the forward barrel band to try to prevent it from coming loose but it no longer remains. Instead, there are pins of some sort on either side, doing a very poor job and instead having caused damage to the barrel band. But as it appears these were placed on the rifle decades ago and likely by one of the soldiers who carried it, I'm content to leave them as part of the rifle's history. The stock is somewhat heavier than that found on my 91/30 but apart from the thickness at the butt, the dimmensions are pretty consistant. With the darker finish, it is possible that this stock is not original but is a Finnish replacement. There is some support for this possibility given that the reinforcing bolt is placed neatly at the back of the gasping groove and not "close enough" as was often the case on Russian stocks (a key distinction between Russian and Finnish rifle stocks.) Whatever the case, it has obviously been with the rifle a very long time.

One alteration that the Finns performed on these rifles was to take the earlier Russian sights, graduated in arshini, the old imperial unit of measure, and restamp them in meters. The result is that one very easy way to identify a Finnish Mosin-Nagant is the presence of two sets of markings on the sight base, one left and one right. In almost every case, the arshini numbers will have an overstrike on them.

The last piece I pulled off this rifle was the butt plate. It was also the most difficult to remove, the screw heads having been severely damaged at some earlier time and over tensioned when replaced. Once I was able to look underneath it, I got a surprise – two, actually. There was a crack in the toe of this stock that I had already noted but, assuming this is the original stock, on a 95 year old hunk of wood, this is not unexpected. At some point, the stock had been drilled out where this crack had appeared, the hole shaped into a sort of dove-tail, and a piece of wood fitted into the hole as a patch and reinforcement. This can readily be seen in the adjoining photograph. I couldn't even begin to guess whether this was done in the field or where but it is an effective means of extending the life of a rifle stock.

More intriguing was what I saw above that patch. At some point, someone had removed the butt plate and either all at once or over a period of time, scratched into the stock four vertical tick marks and a horizontal slash. There is no reason for this marking to be here and I would not expect to find it on any other rifle. Given that this particular specimen was almost certainly fired in anger, one begins to wonder if perhaps the soldier who wielded it at the time was keeping score. The stock shows evidence of fairly hard wear but the markings just noted are a further indication that it's honest wear, that many of nicks and dents were earned on the battlefield and not from a clumsy owner, abusing a rifle they didn't realize carried significant history with it.

Range Tests

One note of caution with the Mosin-Nagant rifles is that bore dimmensions can vary by more than comfortable amounts. From the research I have done, it seems that barrels can vary from .307 all the way up to .315. Finnish made barrels are usually .308 to .310 with Russian made barrels, if made to spec, coming in a .311. If you attempt to fire a .311 slug from a .308 barrel, the restriction could cause dangerous pressures and possibly result in a failure of the cartridge if not the rifle. If you should obtain one of these rifles and wish to fire it, the safest course is to handload your own rounds with properly sized bullets. Conversely, if you have a .315 barrel and a .308 slug, the bullet will not provide an adequate gas seal and may not even engage the rifling. I got lucky on this rifle. Slugging the bore shows a groove diameter of .312.

The next problem to look at is head space. In a rifle intended to fire rimmed cartridges, head space is measured from the rim. One way of looking at it is that this is effectively the allowable distance between the face of the closed bolt and the face of the chamber where the rim rests. Ideal spacing is just enough to allow the bolt to cycle, touching the case head but not putting pressure on it. In practice, there will be somewhat more to allow for the reality that not only will one rifle vary from another but ammunition from different makers and even different lots will have different dimmensions. Too little and the bolt won't close. Too much and the cartridge will not have enough support when it is fired potentially causing damage or failure. Examining the gauges I received shows that the allowable distance is only about five thousantds of an inch. To put that into perspective, a sheet of printer paper is four thousandths of an inch thick. The chamber dimmensions and bolt design didn't change through the course of M1891 production but tolerances one to another will be different. Therefore, if a bolt is not matched to a rifle, or if the bolt head has been replaced, you must question the safety of the rifle. This applies to all rifles, whether military or civilian.

Since I intend to purchase additional rifles of this category, I went ahead and invested in a set of coin type headspace gauges from Yankee Engineers. (A set from any maker with all three gauges will usually run near $100.) This rifle passed with flying colors, no resistance at all on the go gauge and the bolt stopped rotating at about half it's travel distance with the no-go gauge.

That left just one thing to do... burn some powder! Grabbing several generic boxes of shells, I headed down to the range to see how my new friend was going to perform. I will admit to being considerably nervous about firing a 95 year old rifle that hadn't had so much as brush through the bore in probably 30 years, despite the checks I made. When I pulled the trigger and braced myself for this first round, everything went still. At the instant I felt the trigger break, my heart skipped a beat, wondering what the results would be. It was only when I felt the rifle recoil and saw the round impact downrange that I began to relax. Inspecting the cartridge showed no signs of overpressure or hints that there was the potential for failure. Now I could sit down and have some fun.

The Mosin-Nagant rifle of whatever era, off the bench, will wake you up. No such thing as a recoil pad here. If you don't have the butt of this rifle well positioned, you're gonna know it right quick. I've fired so many rounds from older rifles of this sort that I've largely gotten used to it. Yeah, my shoulder still comes home quite tender after a long session but it heals up in just a day or so. Like everything, you get used to it. For me, getting over that threshold makes this class of rifle that much more fun to shoot.

So how did it do? The first target, out at 50 yards, didn't show anything unexpected. Off the bag, groups on this target were pretty even and pretty tight and as expected they were a bit high. Out at 100 yards things changed a bit. With just the leaf sight, it is difficult to get tight groups at that distance but I sure as heck tried. This rifle is right on for windage but since this is not the original sight, I should have expected some variance in the point of impact. With the sight set for 100 meters, the patterns were 6-8 inches high which makes the 100 meter setting near perfect for 300 meters. Hrm.

Each rifle is unique and must be learned individually. It took about 20 rounds for me to start seeing consistancy in the groups but after learning what this critter wanted to do, I was able to compensate for the sight set up and began to get pretty good results. Holding a suitable distance low, 10 rounds on my 100 yard target printed a group measuring 6.6 inches. Ignoring the round that hit low and right and the rest were in a group that was right about 4.5 inches. Taking a few pot shots at the 18 inch and the 12 inch gongs out at the 300 yard line allowed me to hear several gratifying thumps in response. Quite satisfactory.

Really, the only thing about this rifle I didn't like was the action of the bolt. It fed and closed pretty easily but and on opening, unlocked just fine but when it reached the point where it began to extract the case from the chamber, it started to bind up. There were no indications whatever on the casings or at the primer that there might have been any over pressure or hints that the cases wanted to split open but what I was firing that day was also boxer primed steel cased rounds so they might not behave in the same manner we have become accustomed to.

This does not suggest to me that there is necessarily anything unsafe about this rifle, but it does make me wonder if the chamber is not entirely uniform. Before taking this rifle out again, I'm inclined to think that it would be a good idea to take a casting of the chamber to see if I can determine what variances might be present. Alternatively, placing a witness mark on a round to show orientation within the chamber and evaluating it with a micrometer might reveal unusual obturations. One way or the other, more detailed observations are indicated. Of course it is equally possible that this just indicates that I didn't do a good enough job getting all the cosmoline out of the chamber.

Final Thoughts

All in all, I was happy with the performance of this rifle. It fed well, shot pretty patterns, threw up a fairly impressive cloud of dust at 300 yards when I missed the gong (or shards of stone when I was standing and got far enough off that instead of dirt I nailed one of the nearby rocks), kicked like an angry mule, and otherwise seemed to behave just as it should when fired.

That there might be unforeseen issues with a Russian made rifle of this era that by all appearances was carried and used in combat should not surprise anyone and is just further emphasis that one should be particularly careful with older hardware.

I greatly enjoy my collecting activities and ever since picking up my 91/30 have felt the tug of the Mosin-Nagants. I've stated that I intend to get others and if they turn out to have the same sort of character this one has, it's going to be quite a fun ride.

Sep 8, 2009

External Links |

Gun Manufacturers

Cimarron Firearms |

Powder, Primers,

GOEX Black Powder |

AccessoriesBurris OpticsRCBS Leupold & Stevens Simmons Optics |

Favorite Gun ShopsCabella'sCaswell's Guns, Etc Legendary Guns |

Organizations I SupportArizona Citizen's Defense LeagueNational Rifle Association The 9.12 Project The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints The Heritage Foundation The Arizona TEA Party |